A wīl-i žṛāhīm!An Introduction to a Moroccan Queer Language: Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba

A wīl-i žṛāhīm!

An Introduction to a Moroccan Queer Language: Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba

Massinissa Garaoun

12 April 2022

This article introduces the Moroccan Queer[1] language called Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba (HL), which means 'The Moroccan queer speech'. It is an alternative language or anti-language inserted into the Colloquial Moroccan Arabic matrix used by the Lwāba, a Moroccan queer community. The purpose of this language is to make community, along with a language in which its members can recognize themselves, and sometimes communicate without being understood by others. I will offer a contextualization of the sociological and sociolinguistic environment in which the language emerged. I will then document nearly one hundred terms of the HL lexicon, complete with examples and elements of oral literature. To conclude, I will point to theories regarding its origin and future.

Introduction

A body of literature examining Moroccan Darija based or Tamazight-based anti-languages[2] (Secret Languages, Argots, and Slangs) shows that they are particularly widespread in Morocco. These languages show a great diversity of lexical creation processes, using encryption, loanwords from different languages, and language play among others.

I was pleasantly surprised to discover a Queer Language in the sphere of Moroccan argots, that I will call by its main autonym - Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba (HL). I became aware of its existence starting from a biographical article of aHəḍṛāt əl-Lwāba speaker in 2018 (Badi 2016). I interviewed this first speaker, and then, a dozen others, from 2018 to 2020. I was strongly encouraged by them to work on their language, to exhibit their existence, their realities, the proper culture they built, but also their resilient capacity to fight oppression, to create safe communication spaces, and make a community.

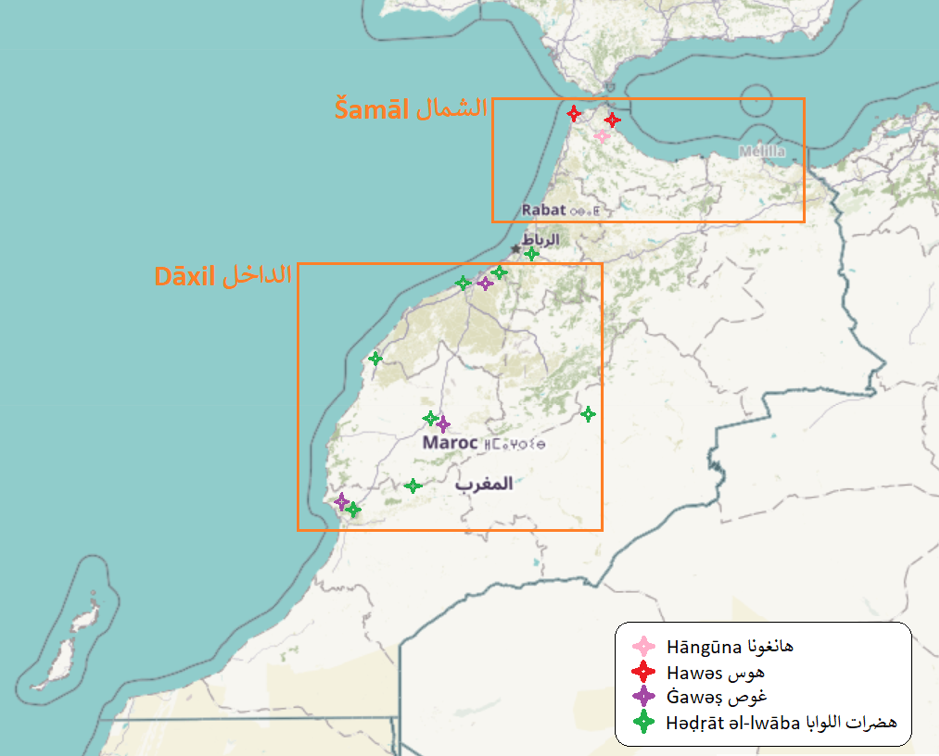

This article will be the first to offer an introduction to this variety, but also to a Queer Language based on Arabic[3]. I am aware that many other Queer Languages are practiced in North Africa, which will undoubtedly be the subject of future research. There is for example at least one Arabic based Queer Language in Tunisia called Gəžmi, several Queer Argots in the main Algerian cities, like the Kəlmātč lə-Ḥbābātč practiced in the Algiers region, among others. In Morocco, I am aware of the existence of at least three other Arabic based Queer Languages: one of them, the Ġawəṣ, is also spoken in the biggest cities of the Dakhil region (Marrakech, Casablanca, Agadir, etc.), while the two others are circumscribed to Northwest Morocco (=Chamal region): the Hawəs and the Hāngūna. (cf. map below).

Yet undetected Queer Moroccan Argots may exist. They might be based on a different linguistic matrix (like the Tamazight Moroccan Languages) and used by other Moroccan gender and / or sexual minority communities.

Data collection

Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba is a set of specific lexicon (group of words) [4] and periphrastic phrases (indirect way of speaking by the use of many words) [5], some grammatical, phonetic, prosodic, and pragmatic features inserted in a matrix[6]: the Colloquial Moroccan Arabic or Moroccan Darija[7].

I collected linguistic and sociolinguistic data from speakers living in the diaspora[8]. The most important part of our lexicon belongs to the Casablanca and the Marrakech varieties, respectively given by Mala and Sadiqa. I also gathered some data from the Salé variety given by Marwan, and the Agadir one given by an anonymous informant. I also notice the Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba use by speakers from Rabat, Kenitra, Asfi, Taroudant, Tiznit and Tinghir, which indicates that the language spread to the south and west parts of Morocco, which correspond to the so-called Dakhil region[9] .

Map of Moroccan Queer Languages

To collect HL's vocabulary, I conducted formal and informal interviews about the specific language the speakers use to converse among themselves as members of the Lūbya Community. Following the first interviews, I asked the new informants about the data already collected, to uncover new vocabulary and to identify possible variations between localities (geographic variation) and speakers (individual variation)

I chose to transcribe my corpus with the Latin characters Colloquially used in Maghrebian Arabic dialectology. My transcription is phonological and will correspond to the urban common dialect (koine) of the Atlantic coastal plains when the specific variety is not given. Notice that the specific features of HL and its speakers brought me to make several choices about corpus translation. First, to respect the diversity of my informants' pronouns, my English translations always use the non-binary pronouns they-their-them. I also decided to not systematically translate some concepts considered by the HL speakers as untranslatable, since they reveal realities deeply rooted in a specific social context.

After collecting the lexicon, I looked for its etymologies to understand the creation/encoding lexicon processes used in this language. I tried to classify these data despite some lexical fields, which allowed me to propose a classification of this lexicon in five lexical fields.

The sociological position of the speakers

The speakers of this queer language define themselves as Lwāba (~ lūbyat ~ lwābi, sing. lūbya). They call the language Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba, a composition that could be translated by 'The Moroccan Queer (Lwāba) Language'. Its lexicon is described as lə-klām əlli ka nəstaɛmlu mɛa l-bɛaḍīyāt-na 'The words that we use together’.

The term lūbya itself means 'Bean' in Colloquial Moroccan Darija[10]. HL speakers give several explanations for its semantic development from a vegetable to a gender/sexual identity[11]. Indeed, lūbya is a term that designates several kinds of gender and sexual identities[12]. Most of the people who designate themselves as Lwāba have been assigned as males at birth, without subsequently complying with the gender expression accorded to males in the Moroccan society[13].

An ongoing semantic shift in the meaning of the word lūbya, appropriated by the Moroccan queer feminist movement, could however be underway (Nassawiyat 2020: 5 & 7), associating this word with all Moroccan gender and / or sexual minorities. Since the speakers insisted a lot about the fact that it is not possible to translate lūbyainto another language - as the identity cluster content in this denomination is specific to Moroccan society - I’ve decided not to translate this word (including its plural form Lwāba) in this work and even in the translations of my glossary[14].

Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba speakers can identify as several gender identities, which could correspond to the English nomenclatures: non-binary, transgender, men, women, among others. They identify as belonging to several sexualities: homosexual, bisexual, pansexual, heterosexual to name some. The only commonality shared by all thelūbya community members is their birth gender attribution in dissociation with their gender expression and / or sexuality.

The second main sociological feature shared by the lūbya community members concerns their social class. A majority of Lwāba are from the Moroccan working class when they do not belong to the lumpenproletariat[15]. Several members make a living or had once from parallel activities, especially sex work. This situation of poverty and pauperization of a whole gender/sexual minority is explained by the oppression they bear in Moroccan society.

It is necessary to insist here on the high degree of stigmatization lived by gender and sexuality minorities nowadays in Morocco. There is indeed a Moroccan law inherited from French colonialism prohibiting same-sex relationships. This law (Article 489 of the Criminal Code) punishes such relationships by 6 months to 3 years of imprisonment and a fine of 120 to 1,200 dirhams. It is important to know that this law is enforced and that it is responsible for many crimes against sexual and gender minorities in Morocco, mostly prison, but also in daily life, since the minorities cannot defend themselves legally against queerphobic aggressions (Nassawiyat 2020).

This legal situation of institutional segregation associated with the social laws of a patriarchal society are, in fact, responsible for the important segregation of the sexual and gender minorities in Morocco. This pauperization leads sexual and gendered minorities to work in parallel economies, reinforcing stigmatization and exposure to violence. This social context is probably the origin of a strong community building and the emergence of the Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba.

Sociolinguistic contexts

The Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba is, as far as I know, only used, learned, and passed on in a specific community: əl-Lwāba. However, outside this community, the code can be learned and used by people who have similar lives. Typically, these are queer and trans people who were assigned the female gender at birth, cisgender women involved in sex work, but can include cis and / or straight men who have been Lwāba partners or friends. Learning this language functions as a rite of passage for new members of the Lūbya Community, since belonging to it signals the understanding and use of its lexical deviations.

This Moroccan Queer Language is strictly oral; the only instance of script sentences showing those languages is an article about the trans non-binary Moroccan activist, Mala Badi published in 2016. However, audio recordings containing HL elements are many, especially on social media: Instagram and Youtube channels made by the community members. The Franco-Moroccan film Zin Li Fik (Ayouch 2015) also contains elements of language drawn from HL.

According to my respondents, the language shows an important geographic variation. A variation that exists between social groups : bəzzāf dyāl əl-lɛībāt ki yəttxəllqu ɛlaḥsāb lə-klīka w əl-mənṭīqa “a lot of concepts are created according to the group and the locality”. The competence level in HL depends on the individual insertion of the speakers in the Lūbya Community, and the practice of the most important economic activity of the community, i.e., sex work in the streets. Indeed, as my data demonstrates, a large part of the HL lexicon is directly linked with sex work. The contexts of the Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba's use are plural: generally, this language is mostly not used in front of outsiders (ma ka nədwīw bi-ha guddām ən-nās maši Lwāba (Casa.) “We don’t speak it in front of the people who do not belong to the Lūbya Community”). But when it is, the words used are rather opaque, unintelligible to outsiders.

There is a sense of pride for a Lūbya Community member to master this language. Becoming a fluent speaker of Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba is a way to demonstrate complete belonging to the community and that the speaker masters its rules and secrets.

Lexicon categories

I noticed early that the HL showed a high geographic variation. This variation seems high and would therefore deserve forthcoming studies on HL be carried out. This geographical variation gives rise to a phonetic variation between the forms in use. Therefore, I will not present generalized phonetic laws of the HL insofar as each geographic community presents particularities often linked to those of the local Darija varieties.

It is essential to specify here that the semantic restitution of most of the lexicon is not an easy task. Indeed, the Argots lexicons sometimes refer to practices shared by a limited number of individuals; often referring to very specific semantics difficult to translate. It can be hard (if not impossible) to explain their complete meaning to an outsider. Certainly, the “quasi-nuclear" meaning, denotative and evaluative, of a slang term, may not always be transmittable. The reasons for their very existence lie in the connotative part of the meaning of slang terms and Colloquialisms (Sorning 1981:1). However, to help the reader, I translated some very community specific words through detail explanations. I also tried to give examples from the interviews for a better understanding of the use of certain lexical items.

Although I will not present the morphological features of this language, I must warn the reader that the grammatical gender does not work here at all as in Colloquial Darija. Which is the reason why this one is not differentiated in the examples. In verbal forms, I illustrate what will be considered as the third person singular accomplished/uncompleted in Colloquial Darija; which is the most frequently used form in HL.

Abbreviations list

v. Verb < Borrowed from

n. Noun > Shift (phonetic or semantic)

a. n. Abstract noun HL Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba

int. Interjection Ar. Arabic

sing Singular Fr. French

pl. Plural Tam. Tamazight (Berber Languages)

e.g. Example Casa. Casablanca Arabic Variety

lit. Literally Agad. Agadir Arabic Variety

Prov. Proverb Mara Marrakech Arabic Variety

Self protection

I was with my new friends, when the party ended, I altered our appearance to look masculine and left, but I still felt like dancing through the streets of Casablanca. [...] My companion Ayoub, or Carol as she liked me to call her, said, “jra girl! There are rouair coming. They’re going to beat you up if you don’t start acting like a guy. (Badi 2016)

This quote illustrates the self-protection use of the HL. This part of the HL lexicon was described by my interviewees as the very first strategy learned by new community members. It is weaponized to protect the community members, although semantic derivation and language play often leads its elements to drift towards more humorous senses.

QŠB (Ar.)

Qəččāb[16] (pl. qčāčəb), n. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija qəššābīya ‘Men djellaba’ (+ apocope and affrication /šš/ > /čč/)

‘Condom’

RŽL (Ar.)

Ṛāṛā (pl. ṛwāyəṛ ~ ṛāṛāt), n. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija ṛāžəl ‘Man’ (+ apocope and syllabic repetition)

1. 'Masculine man who has sexual relationships with Lwaba, e.g., huwwa hada lli fi-h əṛ-ṛəžla w fi nufṣ əl-wəqt huwwa ka yəḥwi l-Lwāba 'This is the one who is masculine and at the same time used to have sex with lwaba’ (Mara.), ṛāṛa ḍaruri xāṣṣ yəkūn mṛāžžəl maši mbənnət 'A ṛāṛa is necessarily masculine no feminine' (Mara.), 2. Man who approaches and seduces Lwāba in order to steal from them, 3. Queerphobic man

(Lūbya) mṛāžžla ~ mṛāžžəl ~ mṛužžəl (pl. (Lwāba) mṛāžžlāt ~ mṛāžžlīn ~ mṛužžlīn), n.

1. ‘Masculine lūbya’, 2. 'Masculinized lūbya', e.g., hiyya ʔaslan mṛa, walakin ka tədīr zəɛma ṛās-ha mṛāžžla (Mara.) 'Although they is feminine, they acts to masculinize themself’

SMD (Ar.)

Smīda, n. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija ‘semolina’

'Anti-HIV antibody', e.g., ka təṭlaɛ fi-ha s-smīda ‘Their anti-HIV antibody level increases’ (Casa.)

SYD (Ar.)

Səyyədāti, n. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija ‘my mistress’[17]

'Human immunodeficiency virus', e.g., ʔāna ɛāyša mɛa səyyədāti mən təlt snīn dāba ‘It has been three years that I live with the human immunodeficiency virus’ (Agad.)

ŽRH (<unknown)

Žṛāhīm ~ Žṛa, n. or int.

1. ‘Danger’, 2. ‘Stop’, e.g., a wīl-i žṛāhīm ‘what a shame, stop this’, 3. ‘Shame on you’, e.g., žṛa ya lə-mṛa ‘Shame on you girl’, 4. ‘Take care’

(Lūbya) mžṛəhma, (pl. (Lwāba) mžṛəhmāt), n.

'Lūbya hiding their belonging to a gender and / or a sexual minority', e.g., hadi ṛa wāḥd əl-lūbya dāyra žṛāhīm, ka txəbbi l-āṣəl dyāl-ha, ‘This one is a lūbya doing like they is not one, they is hiding their identity (Casa.)

Gender identity and performance

This lexicon category is very community specific. Its comprehension is essential to distinguish the most important identity markers in the Lūbya community.

BRHŠ (<Tam. ‘Bastard’)

Lūbya bruhša (Mara.) ~ Lūbya mbrəhša (Casa.) (pl. Lwāba bruhšāt (Mara.) ~ Lwāba mbrəhšāt (Casa.), n.

1. 'Someone who recently joined the Lūbya Community, 2. ‘young lūbya’, e.g., lūbya bruhša yāḷḷāh fətḥāt hnāya‘The young lūbya just opened here’ (Mara.), 3. ‘Lūbya who use to cause troubles’

DMYN (<Fr. domaine 'Field')

Ḍūṃīṇ ~ Ḍūṃīṇa, n.

1. 'Queer person’, 2. ‘Life, identity, experience as a lūbya’, e.g., ʔāna xṛəžt l əḍ-ḍūṃīṇ bəkri (Casa.) 'I am lūbya for a long time', e.g., yāllāh xəržāt l əḍ-ḍūṃīṇ, yāllāh ḥəṭṭāt rəžli-ya f əḍ-ḍūṃīṇ, hadi lūbya əṣ-ṣg̣īra (Casa.) 'They just began their lūbya life, they just put their feet in the lūbya life, they are a young lūbya', ʔāna lli xtārīt had əḍ-ḍūṃīṇ w ʔaftaxəṛ bi-ha ‘I am the one who chose this life, and I am proud of it’ (Casa.) 3. ‘Sex work’

Smīya dyāl əḍ-ḍūṃīṇ (pl. smīyāt dyāwl əḍ-ḍūṃīṇ), n.

'Lūbya's or sex worker's alias'

LṢYN (<Fr. ancienne 'Old (feminine)[18]' (+ agglutination of the French article l’)

(Lūbya) lāṣyāna (pl. Lwāba lāṣyānāt), n.[19], int.

1. 'Someone who joined the lūbya community since a long time', e.g., kūn ma kāynīn š lāṣyānāt bāš ywərrīw-ni kīfāš ndīr fīn nkūn lyūma ‘If there hadn’t been some old ones to show me how to do where would I be today’, 2. ‘Lūbyadescribed as brave, experimented, smart and wise’, e.g., lāṣyānāt ki yəɛarfu šnu ki yədīru ‘The wise ones know what they do’ (Casa.), kūn kənti lūbya lāṣyāna kūn tɛarəf tədwi, ma ġa yəkūn əl-fumm mhərrəs ‘If you were an experimented lūbya you would know how to speak, your mouth would not be broken’, kūni lāṣyāna ‘Be experienced, intelligent, brave’, 3. ‘Elderly lūbya’, 4. ‘Slay, you slay’

Talāṣyānīt, a. n.

‘Sex worker’s expertise’

LWB (Ar. <Persian)

Lūbya (pl. Lwāba ~ lūbyāt ~ Lwābi) n. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija lūbya ‘bean’

1. 'Moroccan person non-normative in gender and / or sexuality assigned male at birth, queer Moroccan person', e.g., hadu huma əl-Lwāba lli hāzzyīn bi-kum ‘This is the Lwāba who supports you’, ṛāžəl maši lūbya ‘Straight man (Lit. a man who is not a lūbya) (Casa), lūbya tmūt ɛla xət-ha ‘A lūbya love their sister (= people)’ (Casa)’, 2. ‘Lwāba ways of speaking, wearing, or behaving, 3. ‘Transvestite’ e.g., kənt ka nxəṛž b əl-lūbya b əl-līl ‘I was going out transvestite at night’ (Casa.)

Talūbyīt (Agad.) ~ Talūbyāwīt (Mara.), n.

1. ‘Lūbya’s knowledge and experience’, e.g., əl-lūbya ma māšya š b əl-flūs ma ɛārfa šnu hiyya talūbyīt ‘The lūbya who does not practice sex work does not know what is the lūbya’s experience’

MRʔ (Ar.)

(Lūbya) mṛa (pl. (Lwāba) mṛāwāt), n. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija mṛa ‘woman’

1. 'Feminine lūbya', e.g., bāyən fi-h mṛa 'They is clearly a lūbya (Lit. in Colloquial Darija ‘Clearly there is a woman inside of they’) (Casa.), 2. 'Trans Woman'

Mṛa qdīma, n. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija ‘Ancient woman’

‘Experienced member of the Lūbya Community’

(Mṛa) məṛmṛa (Casa.) ~ (Mṛa) məṛmuṛa (Mara.) (pl. (mṛāwāt) məṛmṛāt (Casa.) ~ məṛmuṛāt (Mara.), n. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija mṛa ‘woman’ (+ reduplication)[20]

'Very feminine lūbya', e.g., mṛa məṛmura fūq əl-ḥāžra mənšūṛa 'The very feminine lūbya is exposing upon the rock' (Prov. Mar.), mṛa məṛmūṛa ma ka tṛəbbi ġīṛ əṛ-ṛəžžāl ‘The very feminine lūbya doesn’t raise only men (Prov. Mar.)

Tməṛməṛ, a. b.

'Fact to be very feminine, super femininity'

Məṛmṛāt/tməṛməṛ, v.

'To become very feminine, to super feminized

ŠLX (Ar.)

Təšlāx, a. n.

'Sounds, mimics, and body movements that express hyper femininity'

(Lūbya) mšəllxa (pl. (Lwāba) mšəllxāt), n.

'Lūbya who perform hyper femininity’

Tšəllxāt/tətšəlləx, v.

'Express hyper femininity by mean of sounds, mimics and body movements'

ZML (Ar.)

Zəmla, n.

1. 'Queerness’, e.g., zəmla txəllqāt gbəl ma txəlləqti nta ‘Queerness was created before you’ (Casa.), 2. ‘Queer sexuality’, 3. ‘Excitation'

Zāməl ~ Zāmla (pl. zwāməl ~ z(a)wāmīl ~ zām(i)lāt), n.

‘Queer person, fag[21], e.g., ʔāna zāməl, fi xbəṛ əl-lɛālam, w nxəšš-ih kāməl ‘I am a fag, the world knows about, and I put it fully inside’ (Prov., Casa.), ʔāna zāmla, w ka nxəšš-ha kāmla, w b xbəṛ əl-ɛamāṛa (Prov., Agad.) ‘I am a fag, I put it fully inside, and the whole building knows about it’ (Prov., Agad.), ʔāna zāməl qbīḥ w ka ngəls fūq əz-zəbb lə-mlīḥ ‘I am a bad fag and I sit on good dicks’ (Prov., Casa.), kūn zāmla kūn ka nəttḥāwa, ma ka nɛaṭi tta nəmra, tta qəwwād ma sūq-u fi-ya 'Although I’m a fag and I have sex, I don’t give no phone number, so no asshole pisses me off (Prov., Agad.), e.g., zāməl kāməl, u nxəšš əl-hōmōfōb f əl-bṛāməl, w nxəšš fi kərr-hum əš-šəklāṭ ġāməl ‘Total fag, I throw the homophobes into the pot and I put rotten chocolates in their asses’ (Prov. Mara.)

Məzmūl(a) (pl. məzmūlāt), n.

'Excited'

Zəmmlāt/tzəmməl, v.

1 'To sexually excite’

Seduction and sexualities

The next part of the lexicon will be very suggestive by itself. It contains an important part of the HL lexicon, not necessarily because the community members speak more often of these subjects than any other, but because the need to describe and name taboo and forbidden love, desire, and sexual practices is one of HL's raison d'être.

FDR (Ar. FRD)

Fədṛīya (pl. fdāṛa ~ fdādəṛ ~ fədṛīyāt), n. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija fəṛdi ‘rifle’ (+ metathesis)

1. 'Penis', e.g., bġīt ṛāžl-i yəkūn ɛand-u l-fədṛīya dīma mšāṛžīya ‘I want my man to have a penis always loaded (Casa.) 2. ‘Big penis’,e.g., ʔažməl ṭīṭīẓ huwwa lli ɛand-u l-fədṛīya 'The most beautiful beauty belongs to the one who has a big penis' (Agad.)

Fəddṛāt/tfəddəṛ, v.

'To have sex as top, to fuck' ,e.g., wāš bəṣṣəḥ fəddəṛti-ha ‘Is it the truth that you had sex with them as top’ (Casa.)

Ttfədṛāt/yəttəfdər, v.

'To have sex as bottom'

Fədṛīya ɛaḍīma n. + Colloquial Darija 'Majestic, mighty’

'Big penis', e.g., fāš ka tkūn fədṛīya ɛaḍīma ka təbqāy ġa tḥəzzəq mən baɛd ‘When the penis is big you keep farting afterwards’ (Casa.)

Māmma l-fədṛīya ~ Əl-fədṛīya māmma, n. + Colloquial Darija ‘Mommy’

'Huge penis', e.g., ṣīr tšufi ši māmma l-fədṛīya w gəlsi ɛli-ha tšūf ki ġadi tḥəss ‘Go look for some huge penis and sit down on it you will see how you will feel’ (Casa.)

ḤWY (Ar.)

Ḥəwwāy(a) (Casa.) ~ Ḥuwwāy(a) (Mara.), (pl. ḥəwwāyīn ~ ḥuwwāyāt (Casa.) ~ ḥuwwāyīn ~ ḥuwwāyāt (Mara.) ⬪Lit. in Colloquial Darija ‘fucker’

1. ‘Top (someone who prefers to be the person in control during sex)’, e.g., əl-ḥuwwāy l-uwwəl dyāl-ək ɛamr-ək yəttənsa ‘You will never forget your first lover’ (Agad.), 2. ‘Lover’, e.g., ha huwwa l-ḥuwwāy mustaqbal-i ‘Here is my life lover’ (Agad.)

Ḥuwwāy(a) kulši (Mara.), n. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija ‘Fucker of everything’

‘Someone who has sex with both men and women’

ʔaməḥwāy, n.

'Sex'

NWB (Ar.)

Nwība, n. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija nūba ‘round’ (+ diminutive scheme)

'Sexual activity during which the participants alternate bottom and top sexual positions'

ŠWW (Ar.)

Šəwwāya (Casa.) ~ Šuwwāya (Mara.), (pl. šəwwāyāt (Casa.) ~ šuwwāyāt (Mara.), n. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija 'frying rack’

'Versatile (someone who has no preferences regarding anal sex role)', e.g., fāš ka nšəwwīw əl-ḥūt ki yəḍūr bḥāl hakka m əž-žīhāt b zūž bḥāl hadīk əš-šuwwāya (Mara.) 'When we toast a fish, it turns from both sides like a versatile'

Šəwwat/tšəwwi, v. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija 'To fry’

‘To make someone turn sexually bottom’

ẒLL (<Tam. ‘Value’)

Ẓəllāl (pl. ẓəllāla ~ ẓālāʔīl), n.

‘Sex partner' (ẓəllāl ɛa yəlga ši ḥāža ʔuxṛa ybəddl-ək 'When your sex partner finds something else, they replace you' (Casa.), lə-ḥwa ṛa ɛlaḥsāb ẓəllāl-ək nti w ẓəhr-ək ‘Sex depends on your partner, you and your luck’ (Casa.), kulla līla ka nəḍrəb ẓəllāla f əš-šāwarīɛ 'Every night I find sex partners in the streets' (Casa.)

Ttẓəllāt/təttẓəlləl, v.

1. ‘To seduce’, 2. ‘To follow someone to have a sexual relationship’

Parallel economies

As mentioned above, sex work is the main economic activity of members of the Lūbya Community. As an illegal economic activity, requiring rendering visible one’s belonging to a gender and / or sexual minority (which is also legally forbidden), the practice of street sex work is particularly dangerous. But in response to this situation, the Lwāba have developed many survival strategies often aided by the linguistic tool.

BQQ (Ar.)

Bəqqa (pl. bāqq ~ bəqqāt), n. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija ‘Thumbtack'

'Cis woman sex worker', e.g., kāttru l-bāqq 'The number of cis women sex workers increased' (Mara.), əl-ḥūta ma tākul əl-bəqqa ‘A feminine lūbya doesn’t have sex with a cis woman sex worker (Lit. in Colloquial Darija ‘The fish doesn’t eat the thumbtack’) (Prov., Casa.)

DBR (Ar.)

Mdəbbra (pl. mdəbbrāt), n. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija ‘Nifty, resourceful woman’

'Sex worker who finished their performance or working day', 2. 'Ex-sex worker', e.g., gālət-lək lə-mdəbbra, əlli ma žāb-ha b dṛāɛ-u žāb-ha b qāɛ-u 'The ex-sex worker says, whoever did not get it with their strength got it with their ass' (Prov., Casa.)

Dəbbrāt/tədəbbər, v. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija ‘Get along’

'To have sex work performance, e.g., ma dəbbərti ɛla ši ṛəžžāl ‘Did you fail to find men (=sex work clients)’ (Casa.), mšāt tədəbbər ɛla kərr[22]-ha ‘She went to do sex work’ (Casa.)

ʔamdəbbār, a. n.

'Fact to get money (most often through sex work)'

P/BṬRN (<French patronne ‘Patroness’)

Paṭrūna ~ Baṭrūna ~ Žaṭrūna (Casa.) (pl. paṭrūnāt ~ baṭrūnāt ~ žaṭrūnāt)

‘Powerful lūbya and / or sex worker, e.g., əl-paṭrūnāt kazāwīyāt, bla ma təlɛabi bi-hum ‘The powerful Lwāba from Casablanca, don’t play with them’

Tabaṭrūnīt, a. n.

'Powerful behaviour'

ḤŠF (<unknown)

Ḥšəf, n. (Casa.)

'Money', e.g., žəmɛi ḥəšf-ək w ṣīri fḥāl-ək ‘Take your money and go away’ (Casa.)

VKTM (<Fr. victime ‘Victim’)

Vīktīm ~ Vāktīm (pl. vākātīm ~ līvīktīm),

'Sex worker client’, e.g., hadi ka təḍrəb bəzzāf dyāl līvīktīm 'This one has a lot of sex work clients’ (Casa.), a xt-i kāynīn ši vakātīm əl-yūma ‘Ô sister, is there sex work client today’(Casa.)

ƐMR (Ar.)

Ɛamārīya (pl. ɛamārīyāt), n. (Agad.) ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija ‘Bridal palanquin'

'Police car'

Ɛumar, n.

'Money', e.g., əz-zwāməl klāw-līh əl-ɛumar ‘Queer people took his money (Lit.: the fags ate his money’) (Casa.), fāš təlgāy ši wāḥəd ɛand-u l-ɛumar tləṣqi ‘When you find somebody rich you stick (on him)’ (Casa.)

Verbal attack

The last part of the lexicon concerns a kind of oral speech which belongs to the Lūbya community: the Lwāba's verbal attack (=əl-ḥəṭṭān / əl-gūlān dyāl əl-Lwāba). This oral speech uses specific prosody, rhetoric, and poetry. The Lwāba verbal attacks can use both pejorative and ameliorative terms; it can return the mainstream and heteronormative stigmata as well as reinforce them.

FWḤ (Ar.)

(Lūbya) fuwwāḥa (pl. (Lwāba) fuwwāḥāt), n. (Mara.)

'Liar Lūbya', e.g., ši wāḥda f əṭ-ṭrūṭwāṛ tgūl-līk bəlli ši vāktīm dyāl-ha šra-līha ši ləbsa klāṣ[23] w ɛrāḍ ɛli-ha klāt lāpūli, w hiyya ka təḥzəq w ka txərž-līk riḥt əl-ɛadəs 'Someone on a public sex workplace who tells you that one of their clients buys nice clothes for them and invites them to eat chicken meat until they fart, and the smell of lentils comes to you (Casa.)

Fəwwḥāt/Tfəwwəḥ, v. (Mara.)

‘To lie’, e.g., bla ma tfəwwḥi, šəršəmti[24]-līh ət-tərma ‘Don’t lie, you opened your ass to him’ (Casa.)

Fūḥān, n. (Mara.)

‘Lie’

ḤṬṬ (Ar.)

Ḥəṭṭān, n.

'Verbal attacks', e.g., bāš tədīri l-ḥəṭṭān žīb əl-fumm w gūl ‘To do verbal attacks bring your mouth and speak’ (Casa.)

Ḥəṭṭāt/tḥəṭṭ, v. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija ‘To put on’

'To verbally attack someone', e.g., ši ḥaža ɛīb ka tḥəṭṭ-u fi-h 'Something shameful for which you attack him verbally' (Casa.)

(Lūbya) ḥəṭṭāṭa (pl. (Lwāba) ḥəṭṭāṭāt), n.

'Lūbya who masters verbal attacks', e.g., wāḥda ḥəṭṭāṭa ṛa hiyya waḥd əz-zāmla lli lsān-ha maḍi ‘A ḥəṭṭāṭa is a lūbyawho has a sharp tongue’

ʔaməḥṭāṭ, a. n.

'The fact of doing verbal attacks', e.g., əl-Lwāba dyāl ʔāṣtāgṛām ki yədīru ġīṛ ʔaməḥṭāṭ ‘The Lwāba on Instagram are only doing verbal attacks’

QWL (Ar.)

Gūlān, n.

Verbal attack', e.g., ṛa wəɛṛa ɛla mmu-k[25] f əl-gūlān ‘They is so gifted in verbal attack’ (Casa.)

Gəlti, int. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija ‘to say’

'Slay, you slay', e.g., kūn ši wāḥəd lābsa ləbsa zwīna ta tgūl, gəlti ya xt-i (Agad.) 'If someone is wearing beautiful clothes you say, slay sister)

SNN (Ar.)

Məsnūn (Mara.) ~ Məsnān (Agad.), n.

'Gossip’, e.g., ɛand-i wāḥəd əl-məsnūn msəggī b əl-mnūn ‘I have the perfect gossip (Lit. in Colloquial Darija ‘I have a gossip cooked with a melon sauce’) (Mar.)

ŠWH (Ar.)

Lāšwīh, n. ⬪ Lit. in Colloquial Darija šūha ‘scandal’ (+ diminutive scheme and the agglutination of the French articlela)

1. 'Scandal', 2. ‘Outing’, e.g., ila wāḥda ṛa bāġa tədīr-lək lāšwīh, ta ngūlu, əlli ḍrəbna f qāɛ-u ḷḷāh yəmnəɛ sḍāɛ-u 'If someone wants to out you, we say, what we hit in its ass (=the sexual relationship) may God preserve the noise’ (Prov., Mara.)

(Lūbya) mšəwwha(y) ~ mšəwwəh (pl. (lwaba) mšəwwhāt ~ mšəwwhīn), n.

'Scandalous lūbya', e.g., əl-lūbya mšəwwha bḥāl-i, ka təhḍəṛ f əz-zənqa gūddām ən-nās əl-uxrīn (Mara.) 'A scandalous lūbya, like me, they speak in the street in front of everyone (cis and straight people)’

ʔaməšwāh, n, a. n. or int.

1. 'Pleasant moment between Lwāba’, 2. ‘The fact of being scandalous’

Poster produced by Marwan Bensaïd for the Dutch queer feminist organization Tanit, to collect data on the Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba as part of an archive project of the cultural and linguistic practices of the Moroccan queer communities

Theories about HL’s distribution and future

My research uncovered a wealth of information about the convergence and the distribution of Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba. I learned from the lāṣyānāt (the community elders) that the language exists since the 1980s. It is still spoken by young speakers (my youngest interviewee was 20 years old). Its actual distribution seems to extend to all the main big Moroccan cities. Indeed, one of the survival strategies of Lwāba to find more people for their community and attain anonymity is to join big Moroccan cities. For now, the Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba's lexicon collected cannot be used to establish the point of emergence of this language. Indeed, it did not show any lexicon belonging only to a specific geographic Moroccan Darija Variant or Berber language. My interviewees however suggested the possibility that HL came from the mixing of sex worker Jargon[26] with some street slang used by urban teenagers and people acting in parallel economies. Nevertheless, I observed significant phenomena of borrowing, notably grammatical morphology from Berber to HL, which could indicate the development of the language among bilingual communities.

Concerning the future of the language, I observed its use among young speakers: the interviewees were aged between 20 and 40 years. However, some interviewees insisted of the fact that this HL was practiced less and less by young people, and therefore threatened. This might be the consequence of the abandonment of the LwābaColloquial assembly sites: typically, the gardens and other public spaces; dethroned by the recent use of mobile and internet applications. However, according to me, the use of Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba gets significant opportunities to survive, due unfortunately to the marginalization and the oppression of its speaker community. Indeed, in several other queer language contexts, the decriminalization of non-normative sexualities, or gender behaviours caused the loss of the language[27]. The most documented case is the Polari, a British queer language, which is nowadays close to extinction, three decades after the decriminalization of same-sex acts in the United Kingdom (Rosario 2020).

Further, most interviewees reported a behaviour among Moroccan non-heteronormative people characterized by the rejection of the lūbya's identity, language, and culture in favour of others. These identities are associated with so-called international queer culture and history, although stemming from a globalizing and imperialist genealogies that originate in in Western Europe and the USA (Leap & Boellstorff 2004). These are associated with neologisms borrowed from English or Classical Arabic and presented as new and clean from stigma: "They would gather excitedly around me as I talked about love, nature, and gay rights in Europe, using the term mithli (gay) rather than shadh (deviant). I concluded that I was not made from the same mold as Carol and Zbiba so I left them and the world of the louaba. (Badi 2016) They can be interpreted as a phenomenon of acculturation, which might threaten HL in the short to medium term; but in another point of view to extract itself from an oppressive system, to develop new identities and connections with queer people transnationally. In these contexts, the use of HL carries an important political, historical, and social value[28].

Conclusion

“Something in me had changed. In the crowd, a queer person caught my eye and hissed at me “jrahime!” I turned to her and said, “no more jrahime from today on, darling,” and reminded her of feminists and queers who were imprisoned to carve a path for us from the gloomy darkness of prison cells toward the bright sunlight of gender freedom. (Badi 2016)'

This research post is an introduction to HL, the language that a gendered and sexually non-normative Moroccan community, the Lūbya community, created to speak about their realities, to protect themselves, and resist. Despite this first description, a lot of work needs to be done on this variety, and many other lueer Languages based on Arabic dialects. I think that there is an urge to describe those languages, which can be threatened by the strong influence of western queer cultures and languages. There are also a set of questions about queer languages that new surveys could help to answer. For example, what about the existence (or not) of such a language in communities of individuals assigned females at birth? For Morocco, it would be interesting to know about other regional queer languages, especially if some of them are based on Amazigh Languages.

The study I proposed above focused essentially on the lexicon, but I hope for future work to describe the grammatical, phonetical, and prosodic rules of these languages. The sociolinguistic and sociohistorical aspects of this language deserve to be more detailed by looking at its variation and identifying its contact-induced phenomena.

I am very grateful to the Lūbya Community members who helped me accomplish this work. It was a great way for me to participate with others in the construction of an African, an Amazigh, and Arab queer practices archive. A way to apply the empirical anthropological knowledge and the history of these communities, to value them, and to prevent them from being forgotten. I hope that I managed to demonstrate the high level of solidarity and linguistic creativity reached by this community to resist, to survive but also to enjoy life despite the oppression.

[1] I use the term queer here in the global sense of gender and sexual minorities.

[2] I deploy the term anti-language in the sense defined by Halliday (1976:570): “a secret method of communication within a marginalized community created by a kind of anti-society (a society built within another broader and more dominant as a conscious substitute for it).”

[3] The only other extant mention of an Arabic-based queer slang is of a Sîm variety practiced by ‘homosexuals’ in Egypt (Van Nieuwkerk 2012). Jaber (2018) also looked at the specific language practices of Arabic-speaking Levantine Queer Communities.

[4] This lexicon mainly consists of nouns and verbs. Adverbs are rare but do exist (xaṭīr(a) intensifier adverb, mfəxf(ə)x(a) 'Big', etc.), while conjunctions and prepositions are always the same as the Colloquial Darija.

[5] Periphrases are an essential element of this anti-language, a few of them will be given in the lexicon, but specific census work will have to be done about them.

[6] According to the Myers-Scotton terminology (1993) developed for Queer Languages.

[7] [Dāriža].

[8] In France (Paris and Marseille), the Netherlands (Amsterdam) and Spain (Barcelona).

[9] Without indications, the examples are all given in this table (and those which follow) in the Casablanca variety.

[10] This word is widely used among Arabic dialects, after being borrowed from Farsi.

[11] Let me point out that one HL lexicalization process consists of semantic shifts from words originally designating plants and animals to Lwābasocial realities: poplar>police car, thumbtack>cis woman sex worker, fish>feminine lūbya, olive, date, pea, acorn, snail>small penis, etc.

[12] In the brochure of the Moroccan feminist association Nassawiyat (2020:7), it is reported that “before the 2020 outing campaign, this term [lūbya] was mostly used within the Moroccan queer community and was foreign to the broader Moroccan society. However, with the rise of hateful acts and hate speech targeting the Moroccan queer community in 2020, the broader Moroccan society started using the term “Loubya” as an insult. Some members of the Moroccan queer community decided to reclaim this term and started using it to refer to their identity with pride, akin to the trajectory of the word “queer” in English.

[13] See Gouyon (2015) for an anthropological survey of the members of this community in Casablanca.

[14] For example, the Tagnawt and the Taqjimt, two feminine Tashelhiyt Secret Cants [Lahrouchi and or Ségéral 2010], the Lasuniya, the Jewish Traders Slang [Chetrit 1994, Pianel 1950], etc.

[15] Some speakers could have once belonged to higher social classes since they shifted to lower classes because of their identified belonging to a gender and / or sexual minority. Is there an operating marginalisation due to their non-normative gender/sexuality? I’d incorporate this footnote (delete it here) where you talk of the colonial law above. In fact, there is no need for this footnote at all because you explain it well in the para.

[16] The affrication of /šš/ in /čč/ may be due to the lexicalization of this term in HL. I am aware of a similar phenomenon in the Casablanca’ young people's speech: čwīka ‘Peak hairstyle’ < šwīka ‘Little thorn’.

[17] Notice the language play using the different meanings of the word sīda: ‘Mistress’ (<Arabic) or ‘AIDS’ (<French).

[18] The Algerian queer language of the Algiers region borrowed the same French word for the same meaning but with a bit a different phonetic integration: ʔawənṣyāna.

[19] Unlike rural dialects and those of bilingual Arabic-Berber regions.

[20] Note the proximity between these forms and their synonyms in use in the queer language of the Algiers region (həḍṛātᶴ lə-ḥbābātᶴ): mṛāmṛāmṛa ~ mṛāmṛūmṛi. All these forms are produced by the reduplication of the Arabic word mṛa ‘Woman’, with different repetition numbers (two in HL versus three for the Algerian forms) and vowel schemes.

[21] This word can indeed have both a derogative and positive connotation in HL, when it is clearly a depreciative word in colloquial Darija, typically used to insult or designate queer people born as male pejoratively.

[22] In HL, the reflexive is often realized through using the word kərr 'Buttock', while colloquial Darija uses the word ṛās ‘Head’: eg. šəwwāh kərr-u ‘They outed themself’, ʔāna ɛīša b-xīṛ mɛa kərr-i ‘I live well with myself’, ma ɛarəfti š šnuwwa kərr-ək ‘You didn’t know what you were’ (Casa.).

[23] Klāṣ (<fr. ‘Classe’) is a HL adjective meaning ‘Remarkably good or attractive’ and also ‘rich’.

[24] Šəršmāt/tšəršəm (<Tam. Š<S factitive + RŠM<RKM ‘To boil’) is a HL verb meaning the ‘Fact to stretch their anus or vagina’, or the ‘Fact to have bottom sex’.

[25] (Ya) mmu-k(lit. ‘(Ô) your mother’ in Colloquial Darija) is an intensifier adverbial phrase.

[26] The Lūbya culture presents at different levels a certain form of hybridization with the sex work scene. For example, my informant told me that straight cis women sex workers often learned the HL, thus joining in a certain way their group solidarity and practices. This relationship is also supported by the language, a very concrete example is given by the word klīyān (pl. līklīyān ~ klīyānāt), borrowed from French client‘customer’, which designates both a “sex work client” and a “love partner” (with whom there is no economic-sexual exchange).

[27] However, decriminalization does not mean a decrease in violence, as in some contexts it has increased violence against queer communities (e.g., South Africa and corrective rape). This means that the horizon of decriminalization does not necessarily make the use of these languages obsolete.

[28] Just like many other queer languages around the world and especially in the Global South (see Rudwick and Ntuli 2008:446 for IsiNgqumo).

References

Badi, M. (2017). World, I'm a Woman with a Beard and Mustache, Huffpost.

Berjaoui, N. (2007). Notes on Moroccan Arabic Secret Languages, The X… RinC family.

Chetrit, J. (1994). Formes et structures du mixage linguistique dans les langues secrètes juives du Maroc. Caubet D. et Vanhove M.(Éds.), Actes des premières journées internationales de dialectologie arabe de Paris, 519-530.

Gouyon, M. (2015). "Ana loubia": ruses et résistances dans l’exploration identitaire des homosexualités masculines à Casablanca (Doctoral dissertation, Paris, EHESS).

Halliday, M. A. K. (1976). "Anti‐languages." American Anthropologist, 78.3, 570-584.

Jaber, J. (2018). Arab Queer Language: What are the characteristics of the language used upon, and within queer Arab culture, and how does that affect the identity-formation and subjectivity of queer Arab individuals? Institute for women’s studies in the Arab World.

Lahrouchi, M. & Ségéral, P (2010). "La racine consonantique : évidence dans deux langages secrets en berbère tachelhit", Recherches linguistiques de Vincennes, 39.

Leap, W., & Boellstorff, T. (Eds.). (2004). Speaking in queer tongues: Globalization and gay language. University of Illinois Press.

Myers-Scotton, C. (1993). Common and uncommon ground: Social and structural factors in codeswitching. Language in society, 22(4), 475-503.

Nassawiyat (2020), Loubya in the time of corona : Repport 2020.

Pianel, G. (1950). Notes sur quelques argots arabes du Maroc. Hespéris, 37, 460-467.

Rosario, V. (2020). "Gayspeak." The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide, 27.3: 37-39.

Van Nieuwkerk, K. (2010). A trade like any other: Female singers and dancers in Egypt. University of Texas Press.

Hi! My name is Massinissa Garaoun, I am a PhD student in linguistics in the research centre Langage, Langues et Cultures d'Afrique Noire (LLACAN) at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes (EPHE), Paris, France. My work focuses on the description of North African Arabic and Berber varieties of language and the understanding of historic sociolinguistic situations from the phenomena of contact-induced change. I have also been working for four years on the description of Queer Argots practiced by gender and sexual minorities throughout North Africa, including a dictionary project of the Moroccan variety called Həḍṛāt əl-Lwāba in collaboration with the Dutch queer-feminist organization Tanit.