Book Review – Spirit Desire by Sokari Ekine

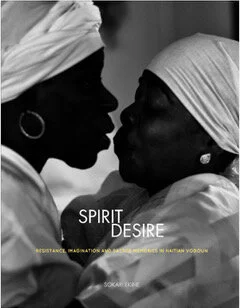

Sokari Ekine, Spirit Desire: Resistance, Imagination and Sacred Memories in Haitian Vodoun (2018)

Reviewed by Alexis De Veaux

Aug 5, 2018

Sokari Ekine’s Spirit Desire, Resistance, Imagination and Sacred Memories in Haitian Voudoun is not meant to be just another coffee table specimen. The series of photographs “made” by the Nigerian British, self-described black queer feminist photographer Sokari Ekine, beginning in 2013, in Haiti, usher in the photographer’s recently published book. As codified by Ekine, the sixty-six photographs (two thirds of which are black and white prints) document ritual, ceremonial, and everyday practices in multiple Haitian spiritual communities known as “lakou.”

In an interview prior to the book’s publication, Ekine corrected my use of the phrase “photographs taken by.” “Taken by”connotes a set of strategies outside her own, an absence of the spiritualrelationship between the photographer, seeing,imagination, and history. “Taken” implies an absence of reciprocity. In the quest for reciprocity between and among black diasporic populations impacted by transhistoric phenomena- enslavement, colonization, trauma, imperialism, racial/sexual/gendered violences, and displacement among them-Ekine’s photographs urge us towards ways of “seeing.” Seeingis different from, is not, looking at.

The photographs articulate Ekine’s visual knowledge ofrasanblaj. According to Gina Athena Ulysse, in Haitian Kreyol, rasanblajtranslates as “assembly, compilation, enlisting, regrouping (of ideas, things, people,spirits. For example, fe yon rasanblaj, means to do a gathering, ceremony, a protest). In this work, rasanblaj recognizes an assemblage of living entities (mental, human, spiritual) conjoined with resistance. Ekine’s description of her work as “queer assemblage,” deploys a radical usage of the term “queer;” one that troubles western notions of LGBTIQ identities; that recognizes the transcendent life between the visible andthe invisible; calls forth multiple intersecting identities framed by multiple, often simultaneous, diasporic and geographic realities; gestures toward emergent possibilities of and for the imagination; and thrives on traditions of resistance and love. Ekine’s “queer assemblage,” then, becomes radical “photo-making;” a disruptive, shifting of the gaze away fromthe “poverty porn” of visual narratives representing Haitian bodies and Haitian spiritual practices, specifically Vodou, and toward celebration of, and the seeing of, the persistence of blackness. Here the desire is less for simplified “positive” readings of blackness; as Toni Morrison speaks of writing to “make the white gaze irrelevant,” so too does Ekine “make” photos that render the white gaze unimportant. As Ekine sees, we see: blackness turns away from that which denounces its power, does not mirror it, and proclaims itself both oppositional to and dominant over. Laying claim to what she terms“the speculative and the subversive,” Ekine’s aesthetic of “making” photographs is constituted not by who is queer, but by what is queer; as “queer” is the interaction between human and spirit, between the known and the unknown, the visible and the invisible, between possibilities.

As such, Ekine’s “photo-making” stands alongside that of black diasporic women writers whose works are, as Carole Boyce Davies allows, aspects of “a growing collage of ‘uprising textualities’….works [that] exist more in the realm of the ‘elsewhere’ of diasporic imaginings that the precisely locatable. Much of [which] is therefore oriented to articulating presences and histories across a variety of boundaries imposed by colonizers […] thereby working on the side of those resisting injustices.”

This is what I see in the cover photograph,“Breath.” The photo appears to be of the embrace of two women. It appears to be of the white cloth framing their black bodies; framing their gaze into each other. The glint of earring. Their alikeness. Appears to be of their centrality to the photo, for there is only them, this headshot. I am transported by the “made” photo; not back in time but across multiple times. Because I am “seeing” and not merely looking, the photograph marks a contemporary moment but its fluidity makes it a portrait of the history of black bodies transported to the so-called“New World;” of bodies that made of the abject trauma of this “New World” a living home for spirit. It is not their breath the photographer helps me to see. It is not whois breathing, but what. In the ritualized moment of Haitian Vodou, in the coming of the lwa, the god(s), what is breathing.

Ekine’s attraction to black and white as primary colors for making photographs can be read as photographic vocabulary; but it can also be read as an intentional political aesthetic. In speaking of his own use of three different kinds of black paint to articulate the figures in his paintings, the visual artist Kerry James Marshall recently stated, “The idea […] is that blackness is non-negotiable in those pictures. It’s also unequivocal-they are black-that’s the thing that I mean for people to identify immediately. They are black to demonstrate that blackness can have complexity. Depth. Richness.” When I read Marshall, I hear him saying “counterpublic.” I hear him talking of the space beyond the orbit, the trajectory, of the dominating narrative. Ekine’s photograph, “Jean Baptiste and Spirit Dog” (although rendered here in color) resonates with the poet Elizabeth Alexander’s idea of “the black interior,” that space “that is, black life and creativity behind the public face of stereotype and limited imagination […] a metaphysical space beyond the black public everyday toward power and wild imagination that black people ourselves know we possess but need to be reminded of. It is a space that black people ourselves have policed at various historical moments. Tapping into this black imaginary helps us envision what we are not meant to envision: complex black selves, real and enactable black power, rampant and unfetishized black beauty.”

This is what I see: not just the portrait of a human and a dog. Not just a human gaze into the camera that is mirrored by a canine gaze away from it. Yes, the human and the canine gaze differently to us, but also the same in the photographer’s lexicon. In the photographer’s lexicon, spirit is “made” known across the stereotypes of human hierarchies, across the prisons of uninspired imagination. The brim of Jean Baptiste’s hat extends beyond his head; on the right side in particular, it extends on the same side as Spirit Dog’s ear extends beyond his head. The hat and the ear are both “listening.” In the photographer’s “seeing,” the two species-members, inhabitants of the lakou- are present for their photographic moment andalert, listening, to what is not visible.

“Jean Baptiste and Spirit Dog”can be read into the idea of black portraiture as a counterpublic. As a counterpublic, black portraiture can signify not simply its tension with white photographic studies of blackness and black bodies, but the desire for a reparative imagination, making more whole how we see the subjectivities of black diasporic peoples. It is the enduring presence of black bodies, the presence of breath, of spirit emanating between us, because of, and for us that situates our lives in the impossible and the possible, simultaneously. Portraits such as “Breath” and “Jean Baptiste and Spirit Dog” announce themselves as alternate public spaces, as aspects of alternate realities; they exist not in opposition to white supremacy, solely, but alongside it, governed by spiritual, cultural, and social laws and traditions within which its inhabitants orbit. In Ekine’s “photo-making,” I enter the realm of the metaphysical.

And this is what I am brought to see: the black bodies of Haitian Vodouizants as conjurations of desire; desire driven not by human need but by the need of spirits. In the photo “Liquid,” I am arrested by the spirit’s strength, its ability to enter, to take over, to possess a Vodou practitioner. I am arrested by the transformationalforceof “spirit desire.” I “see” the spirit that takes her, erect in her outstretched arm. It is virile, demanding, it is both female and male. I “see”her love spirit. I “see” how spirit loves, how spirit love is fierce, disturbing, ugly even, and beautiful. I “see” the water she merges with mutate her legs and they become not-human; they become water. I “see” the water she arises out of become human. I “see” the human become spirit. I see the photograph, the noun, “Liquid,” become a verb, “liquify.” In Ekine’svisual rasanblaj, I “see” how blackness traffics in the impossible.

Water is spirit. And it is also home to spirit. It is the oceanography of our rhizomatics, the spread of our roots as black diasporic bodies, across continents and realities. Water is the cohesive evidence of how black diasporic cultures are rooted in cultural practices of what Ekine identifies as “the Africas.” Just as we do not come from a single transatlantic crossing (arguably, we do not yet know the full extent of the numbers of ships that sailed captured Africans away from home; or today, how many times how many black diasporic Africans make a transatlantic crossing as they journey to and return from countries of the west), just as we do not come from a single “Africa,” we do not come from a single practice of spirit water; we have called these practices Yoruba, Santeria, Candomble, baptisms, Vodou. But we do transmit our understanding of the power of water as spiritual cleanser, as necessary to the right relationship of ourselves to the spirit we are inhabited by and the living spirit of all life-of which we are only particles. In a series of four photographs,“SodoSous,” the photographer participates in a well-known spiritual pilgrimage to the waterfalls, where Haitians pay homage to the lwa, such as Erzulie and Damballah, and where Vodouizants bathe in the sacred waters. Ekine reveals her complex identities as photo-maker and Vodou practitioner; allowing us to “see” her, and therefore what is human, as visible and not visible, as she merges with spatial aesthetics of the natural world, of rock and water and time, her physicality barely there, beneath the water weight, the frightening, unfettered force of it, over her; and the water that is being splashed on her by the mambo, Edeline, and with which she is being cleansed.

Sokari Ekine favors black portraiture. And her work raises questions: what is a portrait of black bodies? How do such portraits operate as sensual realities, as the space of the spiritual in black diasporic lives? How do our images of blackness construct “space” as an axis of the real and the imagined? How do our images read as both noun and verb? The art historian Dr. Salah Hassan offers a way forward. In his theory of the “loci of aesthetics,” Hassan describes the “loci of aesthetics” as filled, active space, locations in which black diasporic peoples deposit and invest cultural knowledges (ie music, dance, body painting, language, speech, dress); this space is what we also recognize by the term black expressive culture. In Ekine’sremarkable photos, freedom itself is a locus of aesthetics. Freedom arrives in the hem of skirts, in the fingertips, in the pliant backs of supplicant black bodies. Freedom is the walls of the lakou, is belief, the belief in the walls to protect against the absence of belief. Freedom arrives in the light in the ceremonial room. And in the sound of that light. It constitutes and materializes the “invisible,”the spirit, so that we are not just looking; we are “seeing.”

http://www.blurb.com/b/8845772-spirit-desire

— Sokari Ekine is a Nigerian British photographer based in New Orleans, USA. She has had major exhibitions in Berlin, Brazil, New York, and New Orleans. You can contact her through her website at sokariekine.me

— Alexis De Veaux, PhD, is internationally recognized as a writer of fiction and nonfiction. The author of numerous works she is widely published and her work appears in a number of anthologies and publications. Most recently she is the author of two award winning volumes, Warrior Poet, A Biography of Audre Lorde (2004) and the novel, Yabo (2014).

Email: luminousleathertoo@gmail.com

Author website: www.alexisdveaux.com